History of US Paper Money

From Colonial Notes to Modern Bills

The history of paper money in the United States is a fascinating tale of innovation, necessity, and economic evolution. From the earliest colonial experiments to the sophisticated Federal Reserve Notes of today, U.S. currency reflects the nation’s growth, struggles, and ingenuity.

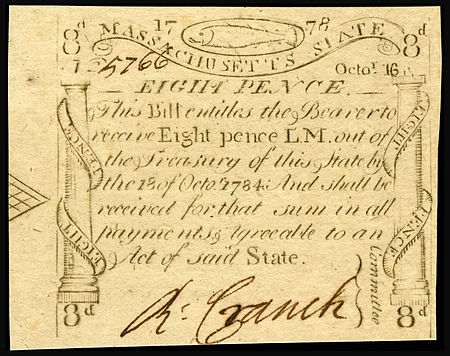

Colonial Currency: The Birth of American Paper Money

The story begins in 1690 when the Massachusetts Bay Colony issued the first “official” paper money in the American colonies. This landmark event was the first instance of government-backed paper currency in the Western world and funded a military expedition against French forces in Quebec during King William’s War. Faced with a shortage of coins and an urgent need to pay soldiers, Massachusetts printed notes promising future redemption in specie (gold or silver). Other colonies, like Virginia and Pennsylvania, soon followed suit, issuing their own paper currencies to facilitate trade and finance public projects.

The Colonial Notes that followed were increasingly adorned with bold designs, early American symbols and sometimes 2 or more colors as an anti counterfeiting device. Many of these notes are prized by history collectors today. While rare specimens can fetch high prices, many remain affordable for enthusiasts. Their historical significance and striking appearance make them thoughtful gifts that connect recipients to the roots of American history.

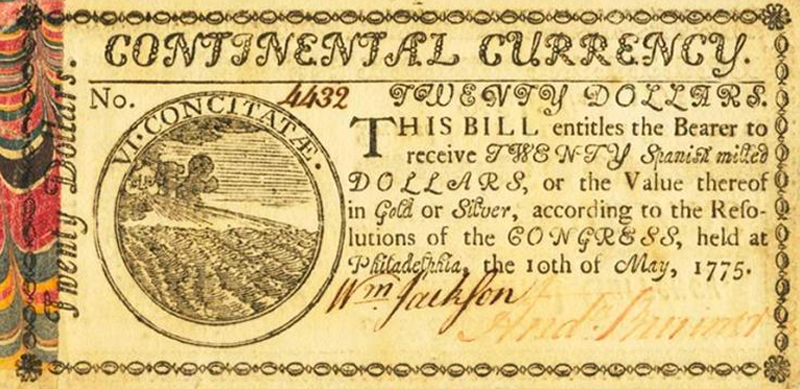

Continental Currency: The Revolutionary Experiment

When the American Revolution broke out in 1775, the Continental Congress faced a daunting challenge: funding a war without a stable treasury. On May 10, 1775, they authorized the issuance of paper money known as “Continentals.” These notes, a milestone as the first national currency of the fledgling United States, were initially accepted by merchants and citizens eager to support the cause. However, lacking precious metal backing and with no taxation system to control their supply, Congress printed vast quantities, over $241 million by wars end. Inflation soared, and by 1781, the notes had depreciated so drastically that the phrase “not worth a Continental” entered the American lexicon as a synonym for worthlessness. Despite their failure, Continentals laid the groundwork for a national currency system. The majority of these notes have been destroyed making the collecting of Continentals excitingly fun & challenging.

Early Federal Currency: Coins and the First Mint

After the Revolution, the newly independent United States sought stability. The Constitution, ratified in 1788, granted Congress the sole authority to “coin money” and regulate its value. On April 2, 1792, the Coinage Act established the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia Pennsylvania. The mint began producing coins, but production was slow, and coins alone couldn’t meet the growing economy’s demands. Small-denomination coins were especially scarce, forcing merchants to rely on foreign coins, barter, or privately issued notes. The need for a reliable paper currency was becoming critical!

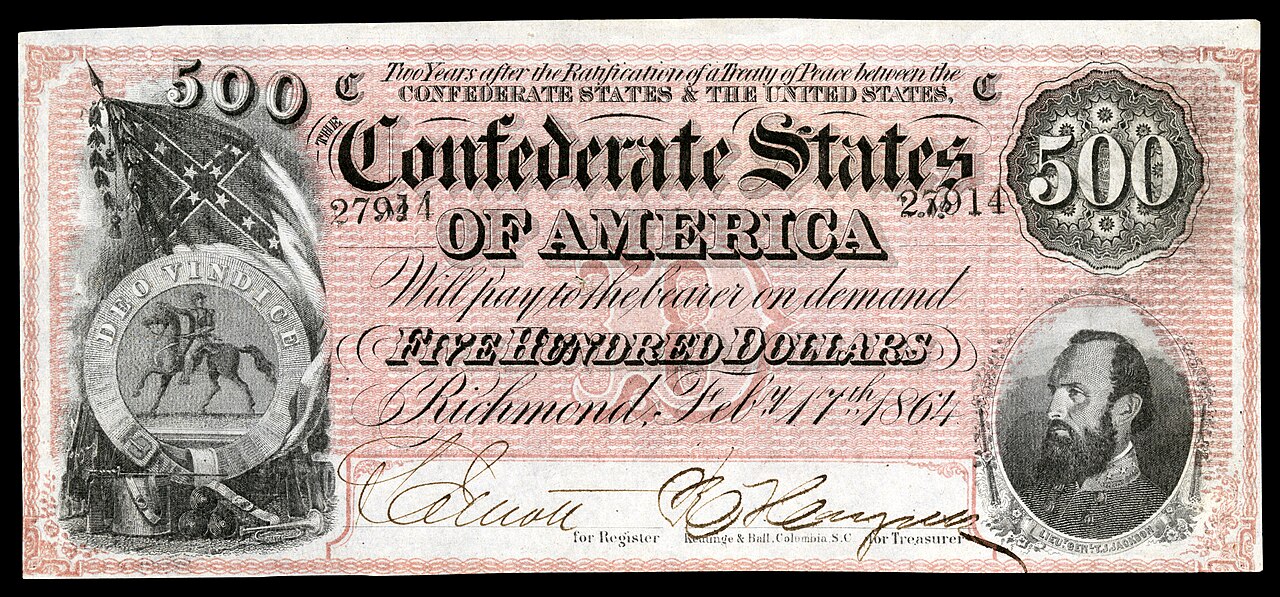

Civil War and National Banknotes: Greenbacks, Confederate Notes, and Broken Banks.

The Civil War (1861–1865) was a pivotal moment for U.S. currency, driving innovation on both sides of the conflict. With war costs soaring, the Union government acted decisively. In 1862, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act, introducing “greenbacks”, paper money named for its green ink. These notes, a milestone as the first fiat currency (not redeemable in gold or silver but declared legal tender by law), funded the Union effort. Over $450 million in greenbacks were issued by 1865, stabilizing the Northern economy despite initial distrust. Meanwhile, the Confederate States of America (CSA) faced similar financial pressures. In April 1861, the CSA began issuing its own paper money, known today as Confederate notes or “CSA notes.” Like greenbacks, these were fiat currency, not backed by specie due to the South’s limited gold and silver reserves. The Confederacy printed over $1 billion in notes by 1865, featuring designs with Southern symbols, leaders like Jefferson Davis, and even enslaved figures reflecting its economy’s reliance on slavery. Early CSA notes held value, but rampant overprinting and battlefield losses caused hyperinflation; by war’s end, they were nearly worthless. Today, CSA notes are prized by collectors for their historical significance, with rare issues commanding high prices but with the majority within the reach of most collectors.

National Banking Acts

The war also exposed the chaos of pre-war “State bank notes,” issued by thousands of private banks & industries across the U.S. Many became “obsolete bank notes” when their issuing banks folded or charters expired. Worse were “broken bank notes,” from failed or “broken” banks, those that went bust and couldn’t redeem their notes for specie, leaving holders with worthless paper. This instability plagued both North and South; though the Confederacy’s weaker banking system amplified the problem. In the North, reform came via the National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864, establishing federally chartered “national banks” to issue standardized banknotes backed by U.S. Treasury bonds. This curbed the chaos, though obsolete and broken bank notes, Union and Confederate alike, remain exceptionally popular collector’s items.

The incredible variety and availability of these notes allow for an array of different ways to collect them. There are many catalogs & guides on these subjects both broad and specialized. Some like to collect a “Type” of each major note while others may focus on one denomination, date or location. However, be aware that tremendous amounts of counterfeits exist with all of these old notes and a wise buyer should seek knowledgeable counsel before spending a significant sum of money. Besides maintaining an extensive inventory of these items, Miller’s Mint is always happy to answer questions and offer guidance and support.

Fractional Currency

The Civil War also sparked a coin shortage, as people hoarded all coins but especially gold and silver ones. To fill the gap, Congress authorized “fractional currency” in 1862, paper notes in denominations under a dollar (e.g., 5, 10, 25, and 50 cents). These small, colorful bills circulated until 1876, when coins returned to prominence. Fractional Currency is readily available today at very reasonable prices although higher grades often command significant premiums.

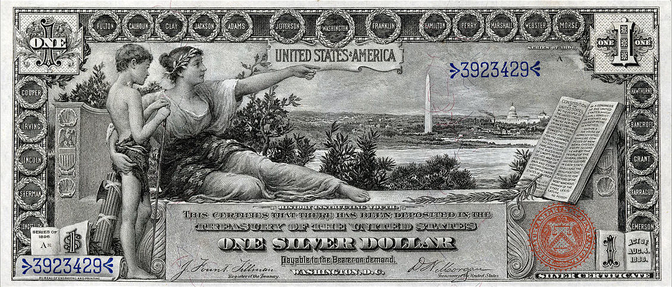

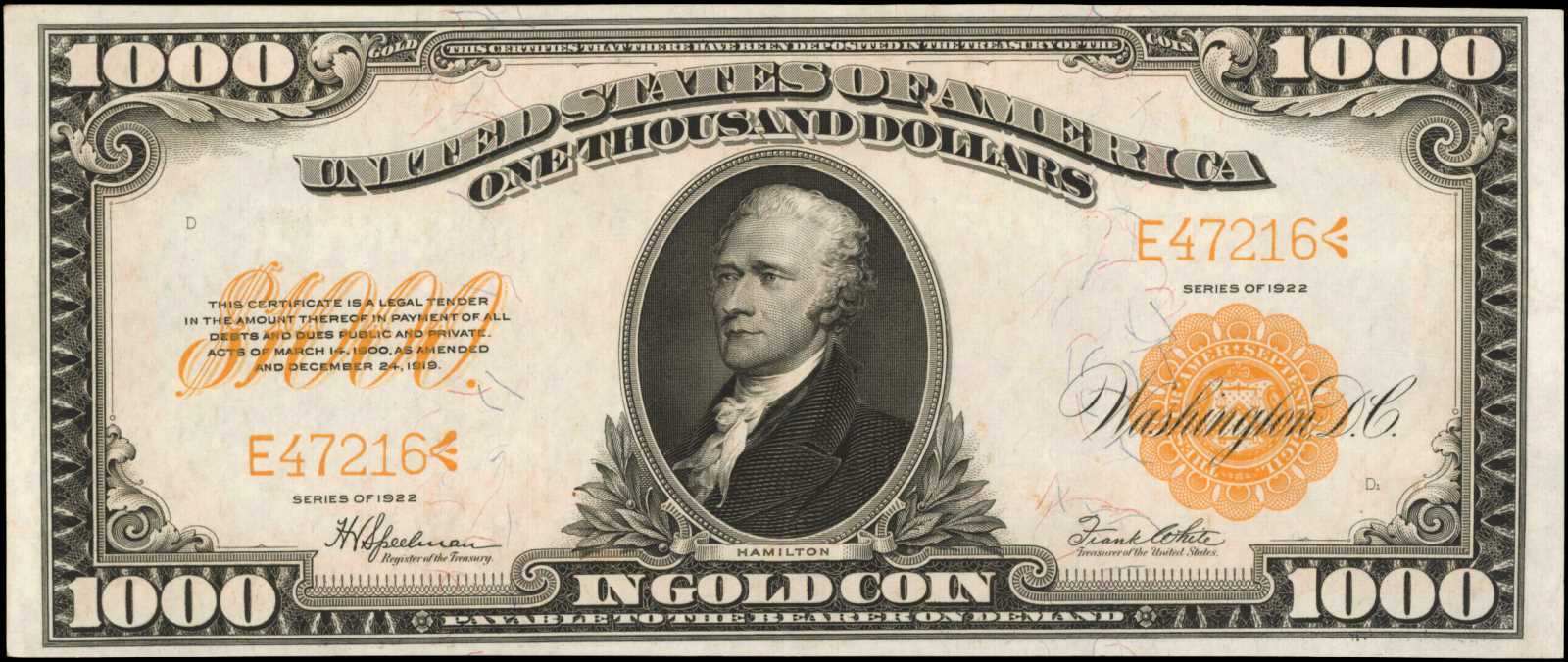

Between the Civil War’s end in 1865 and 1918, the U.S. government issued several distinct types of paper money. The Treasury issued Interest-Bearing Notes and Compound Interest Treasury Notes during and shortly after the war. National Bank Notes were produced by chartered banks under federal oversight from 1863. These extremely popular notes dominated much of this period & featured beautiful intricate designs that are actively collected and traded today. In 1878, Silver Certificates debuted, redeemable in silver dollars and spurred by the Bland-Allison Act to support silver mining interests; they circulated alongside Gold Certificates, introduced in 1865 and expanded in 1882, tied to gold reserves. Federal Reserve Notes, introduced in 1914, solidified their dominance, with a highest denomination of $10,000 although $100 remained the practical ceiling for circulation. National Bank Notes, still produced under the 1863 system, maintained a top denomination of $1,000 as well. These diverse currencies bridged the post-war economy to the modern era, balancing innovation with stability. In the world of Paper Money collecting, this era is the most popular however the Large Size Note a.k.a. “horse blanket” notes, named for their large 7.4 x 3.1-inch size, would give way in 1929 to a new smaller, 6.14 x 2.61 inch design ending a grand era in artistry and design.

The Birth of Small-Size U.S. Paper Money

On July 10, 1929, Federal Reserve Notes led the shift to small size. Ranging from $1 to $10,000, Silver Certificates went small in 1929 as well, ranging from $1 to $1,000 & ending in 1968. National Bank Notes from $5 to $100 remained until 1935. United States Notes, or Legal Tender Notes were denominated in $1, $2, $5 & $100, ceased in 1971 leaving the Federal Reserve Note as the sole currency of the United States but with many design changes. Modern U.S. Currency: Security and Legacy Today’s Federal Reserve Notes are printed in $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100 denominations, blending tradition with technology. Modern notes feature anti-counterfeiting measures like micro-printing, watermarks, and color-shifting ink, refined by the BEP since the 1990s. Each denomination honors historical figures, Washington ($1), Jefferson ($2), Lincoln ($5), Hamilton ($10), Jackson ($20), Grant ($50), and Franklin ($100). One of the most popular ways to collect small size notes is by denomination and series although fancy serial number, errors and consecutive notes are also very popular focuses. In the end, the choice is up to you and Miller’s Mint is here to help with guidance, suggestions and explanations as well as an array of different methods to secure, protect and display your collection.

Happy Collecting!